The Angel of Siberia

Another great Swedish hero of the 20th century who's almost been forgotten.

-

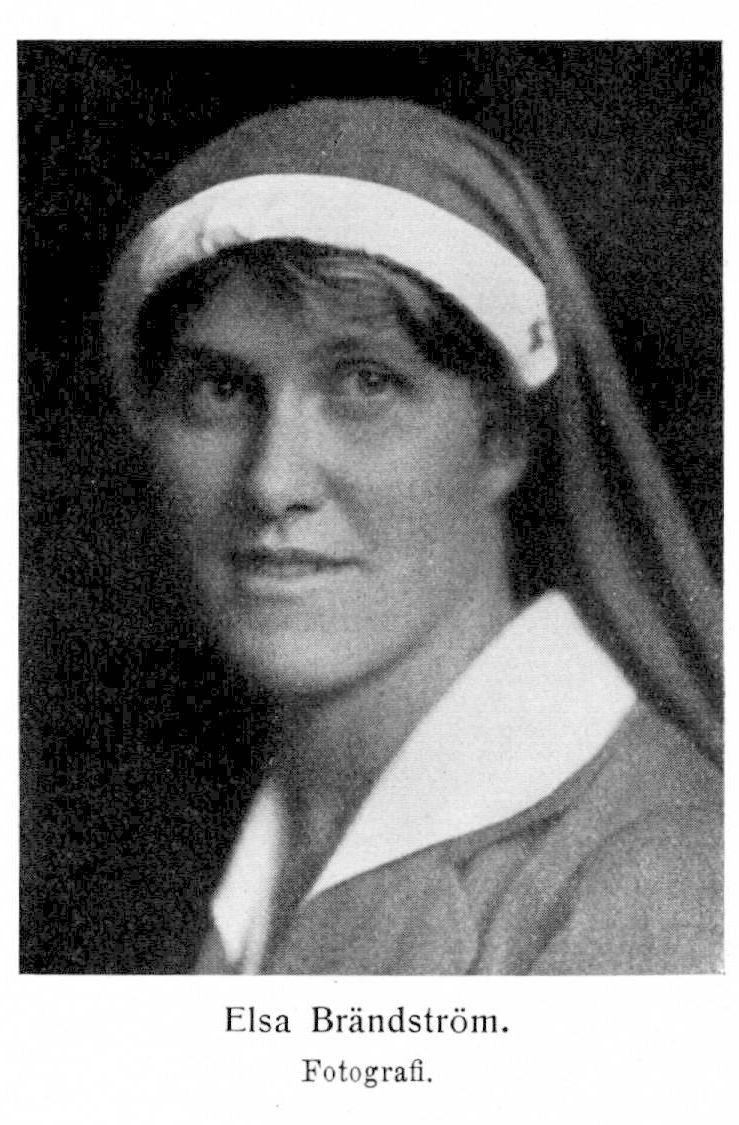

Elsa Brändström, the Angel of Siberia

Elsa Brändström, the Angel of Siberia -

-

Aung San Suu Kyi is a longtime fighter for democracy in her home country of Myanmar (Burma). For her sacrifices and commitment she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. In her speech upon receiving the award in Oslo, she said, “When you are forgotten you die a little.”

-

Memorial for the fallen in WWI in Wurzen close to Leipzig

Memorial for the fallen in WWI in Wurzen close to Leipzig -

-

Elsa Brändström, widely known as the Angel of Siberia, is a great Swedish hero of the 20th century who, unfortunately, has been forgotten.

-

1951 German stamp in a series called "Humanity's heroes"

1951 German stamp in a series called "Humanity's heroes" -

Elsa came from a very distinguished family of public servants. Her father, Edward Brändström, was a highly respected army officer. He was a great believer in the idea of giving back and was a strong supporter of the Swedish Red Cross. Despite being a powerful military leader, he was a kind father and gave his children a happy, liberal upbringing. Elsa’s mother was a warm person with a strong commitment to social justice.

-

Sculpture and plaque in Krems and der Donau in Austria in memory of "Engel der Österr" Elsa Brändström

Sculpture and plaque in Krems and der Donau in Austria in memory of "Engel der Österr" Elsa Brändström -

Edward Brändström was named Swedish military atttaché in St. Petersburg, Russia, where Elsa was born in 1888. In 1891 the family returned to Sweden where Brändström became head of the army garrison at Linköping. Different from the rigid discipline that one might have expected in such a family, the parents encouraged Elsa and her two brothers to be independent, self-confident and involved in social problems. Her mother tried to get her to play with dolls but Elsa was more interested in the town politics she discussed with her father after dinner.

-

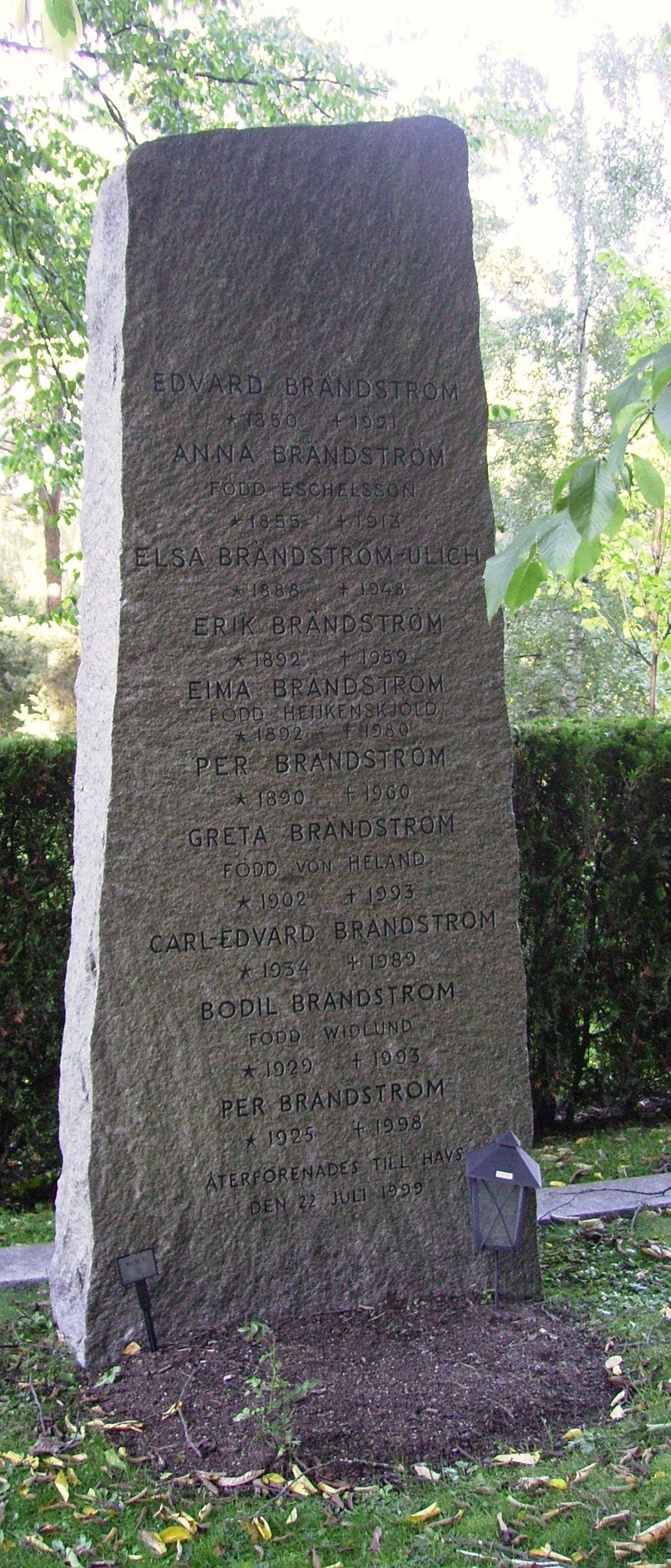

ELsa Brändström's burial grounds at Norra begravningsplatsen, Solna

ELsa Brändström's burial grounds at Norra begravningsplatsen, Solna -

In 1906 Brändström was appointed Swedish Ambassador to Russia, an important and prestigious post. Elsa remained in Sweden, because her parent didn't want her exposed to the overwhelming social life of the glittering Russian capitol at such a young age, and from 1906 to 1908 Elsa attended a finishing school in Stockholm. It was a very bad experience, as she was not interested in the curriculum of embroidery, French poetry and dancing. She wanted reality. The school’s headmistress observed, “Maybe she would fit in in America.” Thus began Elsa's dream of starting her own school.

In 1908 Elsa rejoined her family at the Swedish Embassy in St. Petersburg, the capitol of Czarist Russia. It was a wonderful life of balls and parties, sleigh rides and banquets that Elsa did love and enjoy. Tall, blonde, beautiful and charming, she was the perfect image of a Nordic ambassador’s daughter. But she was conflicted because she wanted also to accomplish something in her own right, in the real world. She wanted to make a contribution against the injustices and oppression that she saw around her in Russia. -

At that time, Elsa met the great Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf. Lagerlöf observed, “One day I went out to see the city, its bazaars and churches, and as a guide I had a young Swedish woman, blonde, beautiful, of the most noble Nordic type. I knew about her that she came from a happy home and since she came from society’s highest circles I could surely imagine that her life was a dance on a bed of roses. But during the excursion this young compatriot began to talk with me of her longing to leave this unsatisfying life of pleasure and make use of her gifts, to do something in her own right.”

-

In 1913 Elsa’s mother died, leaving Elsa as the hostess at the embassy. In 1914 the First World War broke out and Elsa, along with many aristocratic women, trained as a nurse. She visited prisons and hospitals where wounded German and Austrian war prisoners were in transit toward Russian POW camps in Siberia. Elsa saw these men — reviled, helpless, alone — and she realized that as a neutral daughter of a prominent ambassador, she was in a unique position to help these people who had a unique need for help.

-

This realization was a transformative experience and a radical turning point for Elsa. Just as breathing out and breathing in are inextricably linked, so was Elsa’s response to this challenge that she took upon herself. She devoted herself tirelessly to the service of these German and Austrian prisoners held in the farthest reaches of Russia.

-

In October 1915 she took her first trip to visit the Russian POW camps in Siberia. It is appalling to learn that 2.6 million prisoners were held in Russia, 30 percent of whom died in captivity. Friends and family opposed her plans to help in Siberia, it was considered unsuitable work for a woman. But Elsa’s father defended her, saying if his sons wanted to engage in this work he wouldn’t stop them, and why then would he stop his daughter: “No one ought to stop a person from fulfilling their mission in life” was his inspiring comment on the matter.

-

When Elsa came to Siberia with a train full of supplies provided by the Swedish Red Cross, she found that thousands of POWs were kept in frightful conditions. They had little water or sanitary facilities, bad food, inhuman forced labor, no mail or contact with the outside world. They were sunk in apathy and despair. Then “Schwester Elsa” would arrive with a few dedicated helpers. Through the charismatic power of her personality, her noble physical presence and prominent position, she got the Russian camp commandants to cooperate. Elsa came with thousands of “liebesgaben” — backpacks with practical gifts of underwear, gloves, sewing kits, medicine. She obtained for the prisoners infirmaries, better food, clean water and toilet facilities, even the simple privilege of being allowed to take a walk.

-

The physical conditions in Siberia were primitive and Elsa worked despite bitter cold, long distances, poor communications, filth and vermin. She was an extraordinary example of two great virtues: courage and love. At each camp her warm smile and glowing presence gave the prisoners her greatest gift — hope.

-

Very quickly she was called the Angel of Siberia, the Valkyrie of Love. Most of all she restored human dignity to the prisoners. Elsa, who had a glittering social life and many suitors, left her private life behind and dedicated herself totally to the mission of helping the German and Austrian prisoners in Russia. Her electrifying presence was a special gift that made her perfectly suited for this work. There were no limits to her commitment.

-

Elsa was the only neutral Red Cross delegate who saw it all from the beginning to the end. In 1917 the Russian Revolution made her work even harder as chaos and anarchy broke out over the vast land. Several times Elsa was taken prisoner, her supplies were plundered, she was threatened with death. But her mission was clear — to save as many prisoners as she could — and tens of thousands of lives were saved through her efforts on behalf of the Swedish Red Cross.

-

In July 1920, Elsa returned to Stockholm to a hero’s welcome. But she wasn't finished. She wanted to establish several rest homes in Germany for the returning men whose health had been broken by the life in the camps. She wanted to establish boarding schools for the children of those who did not return. She published a book, “Among War Prisoners in Russia” and gave a series of lectures around Sweden as fundraisers to support her cause. In 1923 she traveled to Swedish-American settlements around the United States to give lectures and raise money.

-

Elsa spent the rest of the 1920s working in Germany, where she fell in love with Robert Ulich, a German professor of education in Dresden. They married in November 1929 and had a daughter, Brita, in 1932. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Ulich, a Christian Social Democrat, refused to join the Nazi party and lost his job. The family left Germany and moved to Cambridge, Massachusettes, where Robert taught at Harvard.

-

Elsa could not, however, be content living a private life. As soon as Nazi refugees started arriving in the Boston area, she and other helpers set up the Window Shop, a café where refugee women could learn English, gain work skills and help each other get acclimated to the new country. The shop attracted the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt who visited and wrote about it in her famous newspaper column.

-

In 1939 and 1940 Elsa again toured Swedish communities around America, raising money. Articles in Swedish-American newspapers of the time detail Elsa’s electrifying visits to their communities. During part of her tour Elsa was accompanied by the famous Swedish-American poet Carl Sandburg who paid tribute to her contributions in a deeply moving poem:

-

PRAYER AFTER WORLD WAR -

Wandering oversea dreamer,

Hunting and hoarse, Oh daughter and mother,

Oh daughter of ashes and mother of blood,

Child of the hair let down, and tears,

Child of the cross in the south

And the star in the north,

Keeper of Egypt and Russia and France,

Keeper of England and Poland and Spain,

Make us a song for tomorrow.

Make us one new dream, us who forget,

Out of the storm let us have one star. -

Struggle, oh anvils, and help her.

Weave with your wool, Oh winds and skies.

Let your iron and copper help,

Oh dirt of the old dark earth. -

Wandering oversea singer,

Singing of ashes and blood,

Child of the scars of fire,

Make us one new dream, us who forget.

Out of the storm let us have one star. -

Elsa is the “oversea dreamer,” hunting for donations and hoarse from her many speeches, traveling both north and south in her quest. Sandburg emphasizes Elsa’s greatest quality, that she gave people hope, a star to give as a beacon to follow. The poet refers to the anvils producing airplanes for Norway, the wool making uniforms for Finland, let the copper and iron of America’s mines help endangered Scandinavia.

As soon as World War II was over, Elsa went to Sweden and wanted to go on to Germany to help the thousands of orphaned children, but was not allowed in by the occupation authorities of the U.S. government. Fate had, moreover, caught up with her and she was diagnosed with breast cancer. After an inspiring life of sacrifice, heroic struggle and boundless service she died in Cambridge on March 4, 1948 . Her life can be summed up by the Latin phrase "Probantur tempestate fortes" — The strong are put to the test by the storm. -

Elsa Brändström was the first of four great Swedish humanitarians who gained international prominence in the 20th century. She was followed by Folke Bernadotte, Raoul Wallenberg and Dag Hammarskjöld. All of them met and knew Elsa Brändström. All of them were marked by their Swedish upbringing in which the Lutheran tradition of active service to people in need was pervasive. All of them were crucially aided in their work by Swedish neutrality, especially the international conventions that give special duties, responsibilities and opportunities to neutral states. These four great Swedish humanitarians all had a strong drive for self-realization, to give their life a meaning, to be all that they could be. All of them were faced with a transformative challenge that would change their lives forever. Each one responded with what one can call a transcendent "yes," a total and unlimited commitment. Dag Hammarrskjöld said, “At some moment I did answer Yes, and from that hour I was certain that existence is meaningful.” Each of these four great Swedish humanitarians united the qualities of courage and love to physical stamina, organizational skills and charisma. All enjoyed “flow,” an all-enveloping, all inclusive devotion to a task where nothing opposes the complete fulfillment of one’s destiny.

-

Elsa Brändström is, sadly, rather forgotten now, even in her native Sweden, but she was still remembered and honored in the first half of the 20th century. She served as a model for those heroes of humanity who came after her. She was the one, first and foremost, who saw the task through to the end. She famously said, “They can take my life, but I will reach my goal.” And so if Raoul Wallenberg stayed in Budapest when most of the other neutral countries had left, if Folke Bernadotte left Stockholm for another mediation trip to Israel, even writing his will before he left, if Dag Hammarskjöld flew to N’Dola, risking and losing his life to seek peace in the Congo, we like to think that they were conscious of and following their great model of unsparing humanitarian action, Elsa Brändström.

We still live in a world of massacres, brutal prisoner of war camps, and poisoned gas, but Swedish humanitarians remain inspiring models. It is our duty every day to do the work of memory, to tell and keep telling their story, to not let them be forgotten, to not let them die altogether. Not everyone can devote their whole life to humanitarian action, but everyone can be a humanitarian for 15 minutes of service. I was moved by the Swedish-American woman who came upon a family whose house had burned to the ground and lost everything. She said to the people, “I’m Swedish, can I get you some shoes.” Every one of us can follow Elsa Brändström, even in a little way. -

“Make us one new dream,

Us who forget,

Out of the storm let us have one star.” -

James M. Kaplan Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus of French

Minnesota State University Moorhead

Moorhead, MN 56563 -

-