First Swedish emigrant farmer

Peter Cassel: Another early emigrant from Sweden, arguably the first farmer and leader of the first known larger group of emigrants from the country.

-

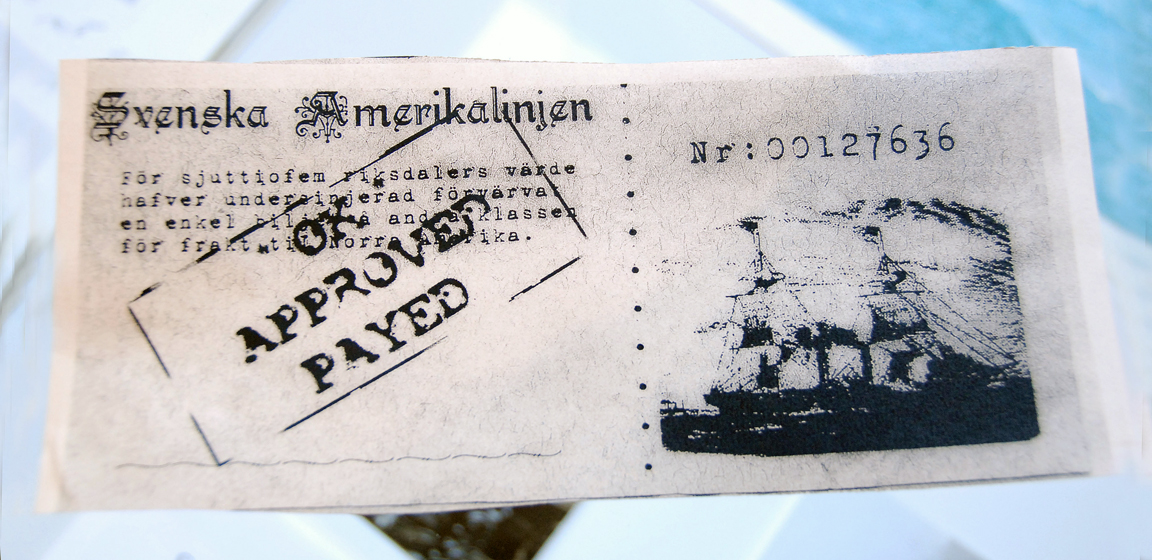

Ticket for the Sweden America Line passage over the Atlantic.

Ticket for the Sweden America Line passage over the Atlantic. -

-

Another early emigrant from Sweden, arguably the first farmer and leader of the first group of emigrants from Sweden. Leaving one year prior to the Janssonites was Peter Cassel of the Kinda region just north of Småland.

-

Makes you wonder what made all of the emigrants leave when you look at images such as this, from Hycklinge harbor in the southernmost section of Lake Åsunda. Photo: Ing-Marie Wallin

Makes you wonder what made all of the emigrants leave when you look at images such as this, from Hycklinge harbor in the southernmost section of Lake Åsunda. Photo: Ing-Marie Wallin -

-

‘Amerikaveckan’

the American Festival in July every other year in uneven years ..not only a homecoming week focused on all Americans of Swedish descent and their relatives in Sweden, but also a recurring celebration with a variety of activities and a meeting place for everyone with an interest in our mutual histories. ..search for your roots, visit the theater, attend a sing-a-long evening, open markets, conserts and much more. -

Hard to beleive that as many as 7,000 people left this region 100 years ago. Then again, this photo of a 19th century shanty is a more adequate depiction of the circumstances of the rural population of Sweden at the time.

Hard to beleive that as many as 7,000 people left this region 100 years ago. Then again, this photo of a 19th century shanty is a more adequate depiction of the circumstances of the rural population of Sweden at the time. -

Also, don't miss our series on Swedish emigration, 'The Importance of being Swedish' Part I: The Fundamentals of the Swedish Immigration or Part II: The Dawn of Swedish America

-

Evening over the Åsunden Lake

Evening over the Åsunden Lake -

Peter Cassel, a well established farmer from Kisa, started a new era in Swedish history in 1845 as he, the first Swedish farmer, planned and organized emigration for a group of 21 people from the farming community in the area. This may be argued as the true starting point for mass emigration from Sweden to America, a full year earlier than Pastor Jansson who left with his much larger group in 1846.

During these first years the emigrants were relatively well-off farming families who sold their farms to finance their future in America. Women emigrated with the group as wives, maids, daughters or older relatives.

Peter Cassel, by his thorough work, created a strong tradition of emigration in Kisa, and the reasons for this door-opener were manifold.

Kisa was overpopulated and people were more heavily taxed there than in other areas of Östergötland province, the larger administrative area. Poverty and drunkenness were rampant. Landowners forced their farm laborers to work hard for almost no pay, or gave them alcohol as pay. The opportunity to escape their destiny didn't exist; society had harnessed them in the social class where they were born. Their job, their food, their clothes, their religion, everything was written down in laws and regulations, and they could not protest since they had no voting rights.

Carl Gustaf Sundius, a well educated pharmacist who had lived in Germany and Denmark, saw the start of emigration. He reacted very strongly to what he saw in Kisa when he started his pharmacy there.

Sundius was very kind and wanted to improve the hopeless situation for the people, so he exchanged ideas on emigration with Peter Cassel when he came into the pharmacy. Cassel had by political actions tried to improve the situation for the people of Kinda, but he had failed, and he didn't see any other option but to leave the country. Sundius helped him financially by selling his home and later his pharmacy to see Cassel's group underway. In May 1845 the group left—first by canal boat to Göteborg, then across the Atlantic on a brig called “The Superb,” which brought them to America within eight weeks. -

The Emigrantmuseum of Kisa, housed in the same building as a café along the main route through town, exhibits records and memorabilia of Peter Cassel and other emigrants from the area Photo: Ing-Marie Wallin

The Emigrantmuseum of Kisa, housed in the same building as a café along the main route through town, exhibits records and memorabilia of Peter Cassel and other emigrants from the area Photo: Ing-Marie Wallin -

The motivations for leaving

Cassel's motivations for leaving were many: political, financial, social and religious. He was controversial because he could explain to simple people the contentious issues of why they lived in such poverty.

He wrote home from Jefferson County, Iowa, in February 1846: “Freedom and equality are inscribed in the Constitution of the United States. Here there are no counts, barons or wealthy owners of mansion houses. One person is as good as the other. A Swedish peasant is transported into a new world, where his dream of a life in accordance with the laws of nature are realized, and here he enjoys life like never before. There are no beggars here, because of the generous spirit of the people who live here. It is easy to make a living, and we are happy and satisfied."

He goes on to describe in detail what things cost, and how there is an abundance of products from farming—wheat, corn, pumpkins, cucumber, beans and how animals like swine, turkeys and cows are all bigger and yield more than in Sweden. There are no taxes, except on distilleries, and you don't even have to lock your house if you go away. There are no thieves. People on the whole are nice and help each other. And they don't drink. I have had dinner in hundreds of houses, but I have never seen a bottle on the table anywhere."

Land was bought for $1.24 an acre and the group bought 1,000 acres of fertile land on the river Des Moines. Germans who lived in the surrounding area were said to be “industrious” and Americans a kind and well-meaning people, always ready to help.

Peter Cassel organized the building of a church in New Sweden. It was the first of the Augustana Lutheran Church. In a letter in 1848 he wrote his brother in Sweden to send a number of hymn books and books of chatechism, because the old ones had gotten so worn they could no longer be used. A Swedish preacher had arrived, so going to church and studying the Bible became a regular part of life.

In 1850 a Methodist preacher arrived in New Sweden and most of the people in the congregation converted to Methodism. In 1851 Peter Cassel himself took over leading the congregation for three years following the preacher's departure. -

Kinda Kanal, which is really an extension south of Göta Kanal through Lake Roxen.

Kinda Kanal, which is really an extension south of Göta Kanal through Lake Roxen. -

"America-letters"

In his letters, Cassel continues to describe life as he found it in America and the result was that more and more people wanted to leave Sweden. Cassel even wrote to say that help would be organized for those who could not pay their ticket, and they could pay back when they had arrived and gotten a job.

His letters were not readily accepted in the Old Country. Conservative newspapers tried to paint him as a dreamer and liar, but that did not stop ever more people to leave Sweden.

The first emigrants, like Cassel himself, were farmers who became farmers in America as well. Increasingly, emigration changed: Lumberjacks and iron miners were recruited directly by company agents in Sweden, and agents recruiting construction workers for the American railroads began appearing in 1854. Emigrant guidebooks were published to help people with practical advice on how to manage upon arrival.

The iconic "America-letters" describing life to the people back home sometimes led to chain reactions which would all but depopulate Swedish parishes, only to reassemble them in the midwest.

The cost of crossing the Atlantic dropped by more than half between 1865 and 1890, making it possible for poorer Swedes to go. Younger and unmarried immigrants shifted emigration patterns from family to individual emigration. These people took whatever jobs they could get and were more quickly Americanized. Many of them stayed in the cities, especially in Chicago, which was for some time the second largest Swedish city in the world with more than 100,000 Swedes. Only Stockholm had more Swedish inhabitants. -

Kisa Hembygdsgård and the church boat during the "Amerikaveckan"

Kisa Hembygdsgård and the church boat during the "Amerikaveckan" -

From simple life to sophistication

Women, young and single, most commonly moved from field work in Sweden to jobs as live-in housemaids in urban America. As domestic servants they were treated as members of the families they worked for, and American men showed them a courtesy and consideration to which they were not accustomed at home. They were in high demand, and learned the language and customs quickly. They usually married Swedish men, and brought with them in marriage ladylike American manners and middle-class refinements. Simple Swedish farm girls gained sophistication and elegance in a few years.

A girl wrote to a friend in Sweden, saying she bought 17 dresses in one year. Ready-made clothes were cheap, and one can imagine what a farm-girl in Sweden thought about that. She probably wouldn't have 17 dresses in her lifetime.

Anglo-Americans looked upon Scandinavians as good people. "They are not peddlers nor organ-grinders nor beggars, and they do not seek the shelter of the American flag merely to introduce among us communism, nihilism or socialism." They were also welcomed as Protestant counterweights to the Irish Catholics. -

Reenactment in Kisa during "Amerikaveckan".

Reenactment in Kisa during "Amerikaveckan". -

Emigration dropping with better times

Before the turn of the 20th century, Swedish emigration dropped dramatically, as conditions in Sweden improved. Sweden underwent a rapid industrialization and wages rose, especially in the fields of mining, forestry and agriculture. The price of land in the U.S. rose, and the U.S. was haunted by labor unrest. In Sweden, a Parliamentary Emigration Commission was instituted in 1907, which recommended social and economic reforms in order to reduce emigration by bringing "the best sides of America to Sweden.” Among the measures proposed were universal male suffrage (women got the vote in 1921), better housing and broader popular education. When World War I broke out, emigration was reduced to a mere trickle. From 1920, there was no longer a mass Swedish emigration.

From 1845 till 1915 around 7,000 people emigrated from Kisa and surroundings. Kisa has an Emigrant Museum (In the Café Columbia building) where records and memorabilia of Peter Cassel and other emigrants' history are preserved. -

The iconic "America-letters" describing life to the people back home sometimes led to chain reactions which would all but depopulate Swedish parishes

The iconic "America-letters" describing life to the people back home sometimes led to chain reactions which would all but depopulate Swedish parishes -

Sources: Anna Olsson, Kinda Kommun

-

Midsommar at the Åsunden Lake

Midsommar at the Åsunden Lake -

Find out more about Kinda and the surrounding area at www.kindaturism.se

How to contact Kinda tourist office:

Phone: +46 494-194 10,

Email: turistbyran@kinda.se -

Cruising Kinda Kanal. Photo: kindaturism.se

Cruising Kinda Kanal. Photo: kindaturism.se -

Swedish Tourist boards official website:

www.visitsweden.com

Cruising or boating on Kinda Kanal, www.kindakanal.se/ or Göta Kanal, at www.stromma.se/Gota-Canal/ -

-