A life less ordinary

Legendary fashion photographer Gösta 'Gus' Peterson passed away at 94.

-

Gösta's iconic spread for the New York Times. Lesley Hornby, better known as Twiggy.

Gösta's iconic spread for the New York Times. Lesley Hornby, better known as Twiggy. -

-

Friend and subscriber Gösta 'Gus' Peterson passed away on July 28 in Manhattan. He was 94.

-

Stroboscopic light effects, today added after the photo session, were created manually by Gösta in the early 1970s, by using a rotating light and different exposure and shutter techniques.

Stroboscopic light effects, today added after the photo session, were created manually by Gösta in the early 1970s, by using a rotating light and different exposure and shutter techniques. -

-

Gösta was a Swedish born, self-taught illustrator and photographer who made fashion history many times over for his iconic photography of up and coming models for Henri Bendel ads along with several covers for the New York Times Magazine.

-

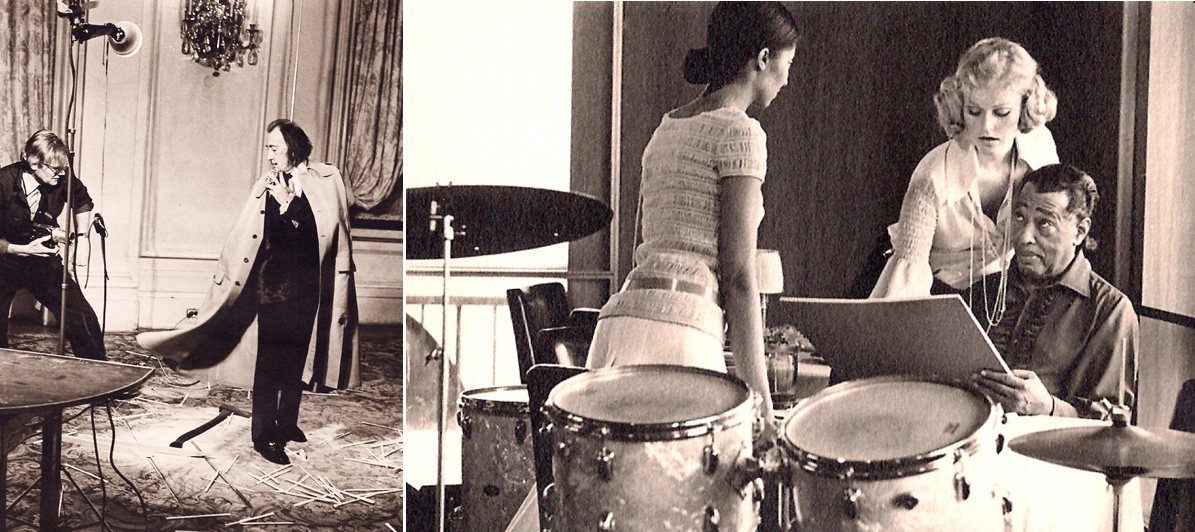

Gösta, captured while setting up to portray Salvador Dali for the New York Times Magazine; Duke Ellington, 1969. Sitting for a fashion editorial for The New York Times Magazine

Gösta, captured while setting up to portray Salvador Dali for the New York Times Magazine; Duke Ellington, 1969. Sitting for a fashion editorial for The New York Times Magazine -

We feel privileged to have met and gotten to know one of New York's most stylish and intellectually sharp nonagenarians. For one whose life covered so many facets, Gösta Peterson never lost his devotion to his family, his countries or his friends. Vila i frid Gösta, your optimism, your sharp insights and never ending energy will be sorely missed.

Ulf Barslund Martensson -

Gösta Gus Pettersson, the yes man, goes on shoots for Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, every major fashion magazine, the New York Times Magazine...

Gösta Gus Pettersson, the yes man, goes on shoots for Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, every major fashion magazine, the New York Times Magazine... -

From our earlier portrait: 'The Career that almost didn't happen' (2011)

Legendary fashion photographer Gösta Peterson was part of honing the art of communicating fashion in the early days of fashion and glamour magazines. But photographer Gösta Peterson’s is a great career that almost didn’t happen.

As a young man who’d just arrived to America, he was waiting for a train to take him to New York, when calamity struck:

“I was so worried I’d forget my portfolio with drawings that I sat on it, but I was also excited about New York so when the train pulled in I rushed onboard.”

Left on the bench at the Philadelphia train station: the drawings.

Now fortunately a conductor called the station in Philadelphia and luckily Gösta’s portfolio was shipped to New York where soon he relocated and began his illustrious career. It was 1948.

But let’s get back to the beginning.

In Gösta’s case the beginning was Stockholm in 1923, when he was born. His family included no artists or photographers – his father owned a delicatessen store – but Gösta liked to draw and was good at woodworks and sewing at school in Örebro, the city his family soon moved to and in which he grew up. Eventually, he studied and became an illustrator and worked at an ad agency in Stockholm. That’s when a relative in America invited him to come over.

“I was young, and I wanted to see the world,” says Gösta. “And here was a relative that we all presumed was dead, and he invited me and gave me an affidavit, something you needed in those days in order to get your papers.”

Thus he finally ended up in New York with his portfolio intact, living at a YMCA and walking the avenues looking for jobs. He finally landed a job at Lord & Taylor as an illustrator, eventually got himself an agent and access to a studio. -

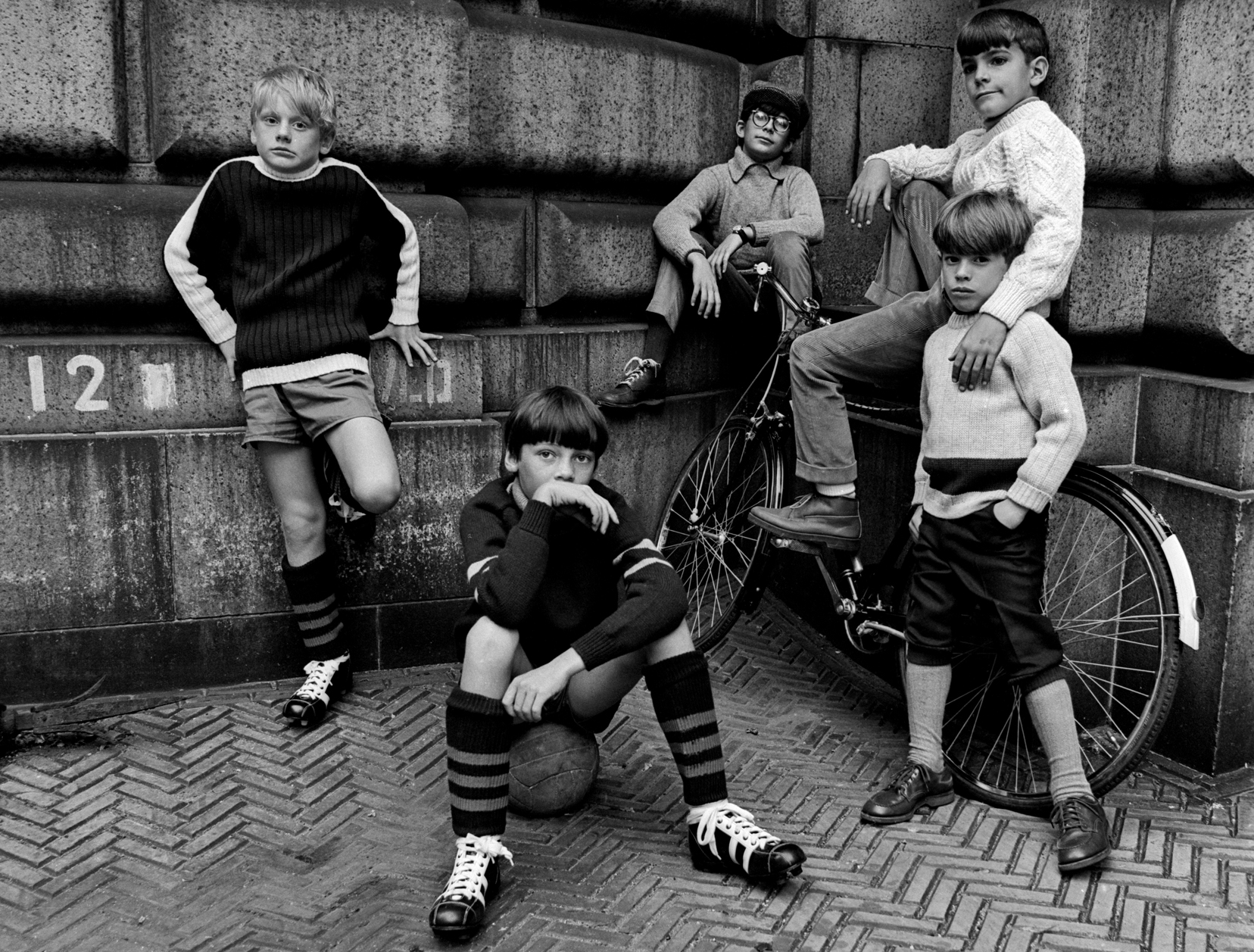

A group of New York school boys photographed for The New York Times.

A group of New York school boys photographed for The New York Times. -

The idea man

“I had ideas and I loved drawing and it was fun,” remembers Gösta. “But little by little I got tired at having everybody fiddling with my drawings. It was never right, they always wanted to change something in the ads I did. So I began thinking. When I left Sweden, I was given a Rolleiflex camera as a goodbye present from Gumelius Advertising Agency where I had been working, and I had this notion that photographers traveled the world and met a lot of girls, it sounded like good times, so I thought why not become a photographer?”

Armed with a book of camera instructions, Gösta again took to the streets of New York in search for inspiration and objects for his camera lens. When I asked what he thinks it was that he had that made him stand out as a photographer almost immediately (since it certainly wasn’t training), Gösta says:

“I had good ideas and I could communicate well with the person I photographed. I always had my own ideas and I was never anybody’s assistant. Sometimes I captured what I call a ‘lost moment’, and that made it interesting.”

He was also willing to work, and was quickly nicknamed “Yes”, since he always said yes to everything. When he heard somebody at “Mademoiselle” magazine say: “We’d better get him before anyone else does”, he realized that he might have a good career ahead of him as a photographer. His photo career began to really take off somewhere between 1955-1960. By then he had met his wife-to-be Patricia at a cocktail party. They were married in 1954 and have two children: Jan and Annika.

“Whether you’re drawing or taking photos, it’s really the same technique,” Gösta explains. “At least when it comes to composition, lightness and darkness.”

It was his ads for Henri Bendel, which ran from the late 1960’s into the early 1980’s, that made Gösta something of a star photographer. One ad a week, he shot for them.

“They’d call on a Tuesday, on Wednesday they’d have the models and clothes ready, we’d shoot on Thursday, they’d have the photos on Friday and the ad would be in New York Times on Sunday. All of them were half-page ads. I was expecting these calls, it was never boring or difficult – it was always fun.”

Looking at these ads today, what’s striking is their sense of freshness, the imagination and originality in them. One of them shows a group of girls on roller skates, looking like they might fall any minute.

“Well,” said Gösta. “I knew of this spot in Central Park, a fun place with lots of graffiti, and as usual I wanted unknown girls, I never wanted to work with top models, so I said to the agency to just make sure the girls knew how to roller skate, because I thought that might be fun! We got the skates, the girls came and they said that yes, they knew how to skate. Put the skates on them and they fall, one after the other. But it made a great picture!” -

Gösta “Gus” Peterson, in front of a poster of photographs from a shoot for a 1967 New York Times with Lesley Hornby, a.k.a. Twiggy.

Gösta “Gus” Peterson, in front of a poster of photographs from a shoot for a 1967 New York Times with Lesley Hornby, a.k.a. Twiggy. -

Always on the lookout

Gösta’s pictures were quickly recognized and put in photography magazines, illustrating how to compose photos in different ways. Looking at the hundreds if not thousands of photos spread out on the tables in his son’s Tribeca apartment, I can’t help but ask:

“Did you always carry your camera with you?”

“No,” he answers quickly. “But always my head!”

And his eyes of course. Gösta was always on the lookout not so much for beautiful but interesting people. Once he found a girl with broken glasses in the street, that he felt looked “different, interesting”, gave her his card and when she called, he used her in one of those Henri Bendel ads, one for fur. Another time when he and his wife Patricia had dinner at a restaurant, he saw an interesting girl across the room, walked up to her and asked if he could photograph her. The man who was with her was not too pleased.

“It was Philip Roth, the author,” says Gösta with a laugh. “But I didn’t know that. My wife told me. He was probably upset that I didn’t want to photograph him.”

Though Gösta didn’t like using the top models of the day, he made an exception when in the 1960’s he photographed a star.

“New York Times wanted me to do something on this new big model from England. Clothes and hat had already been chosen. She came to the studio and she was great. Yes, of course she was.”

Her name: Lesley Hornby. Better known as Twiggy.

The photo: An almost iconic Twiggy photo in black and white with a close up of her face with the enormous eyes and smatter of freckles in which a full-body photo of her is superimposed.

Gösta also photographed the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali at a hotel room in New York City for Esquire Magazine.

“The subject was capes,” Gösta remembers, “and Dali wore capes. He wanted only three things for the shoot: sugar, straws and an axe. I just thought that was fun! He was crazy but willing. We got the sugar and we got the straws, but it was harder to find an axe, until we pried one out on one of those fire alarm boxes.”

The result? An as always crazed-looking Dali furiously axing the air in a rain of sugar standing on a floor covered with straws.

There’s a lot of this kind of movement in Gösta’s photos, but his trademark is really the composition, the flawless composition. His is more art photography than anything else.

It was also in the 1960’s that he began experimenting with solarized photography, after having seen Picasso’s solarized illustrations in an art magazine. The solarized photos are beautiful and went well with the geometrical fashion of the times, though they might look a bit dated today.

Another frequent model in Gösta’s photos is Duke Ellington, who was a dear friend.

“I’d call him up for a fashion shoot and he’d come on down. It was fun because Duke liked girls. But I don’t think his musicians friends liked it all that much.”

Of today’s fashion photography Gösta doesn’t think much.

“Have you seen it? It’s terrible! The girls are all too made up and then they just sit there in the center and stares into the camera! There are no ideas!”

He also says he cares more for style than fashion.

“It’s what it is,” he says when I point to a photo of a woman with ridiculously high heels. “It’s not whether I like it or not. I just do something with it. I’m interested in different things, I like people who have their own style, it’s fun to get that into the photos. Fast trends are negative, it’s style that’s interesting to me.”

When I ask who he thinks has style, he mentions painter and illustrator Richard Merkin, the “old Swedish king” (Gustaf VI Adolf), and Winston Churchill.

Looking back at his life, Gösta neatly sums up what set him apart and gave him a wonderful, adventurous career.

“You have to take chances. Most of the time I was fairly sure that a photo was going to turn out OK, but I was never completely sure.” -

Photographs courtesy of Gösta Peterson

www.gostapeterson.com -

26-27 New Mexico, 1971. Gösta is shooting for a photo feature on Native American children when he spots an interesting look in Albuqueque. The youth agrees to model if his friend can join. The hat stays on.

-

28-29 Gösta Gus Pettersson, the yes man, goes on shoots for Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, every major fashion magazine, the New York Times Magazine

-

30 Tehran, 1969. In Iran to photograph Farah Diba, who refuses to have her photo taken because she is pregnant. Gösta’s editor simply asked him to find “someone else” and he found an renowned violinist whose portrait he took.

-

31 Tunisia, 1978. Shooting bathing suits for the French magazine L’Officiel

-

32 Gösta, captured while setting up to portray Salvador Dali for the New York Times Magazine.

-

Gösta's iconic spread for the New York TImes. Lesley Hornby, better known as Twiggy.

-

33 Stroboscopic light effects, today added after the photo session, were created manually by Gösta in the early 1970s, by using a rotating light and different exposure and shutter techniques.

-

34 1969. Duke Ellington. Sitting for a fashion editorial for The New York Times Magazine

-

35 A group of New York school boys photographed for The New York Times

-

-